Graduates looking for their place on the labour markets of small towns and villages are doing no worse than their peers from big cities and agglomerations In many respects, graduates from small towns are even more effective, as shown by the data from the Polish Graduate Tracking System (ELA). This dispels another myth – that of the small town as the place without prospects.

Among many stereotypes about careers there is the belief that if you want to succeed, you have to move to a big city.

It is widely believed that that small towns and the countryside deserve to be called “Poland B” – a place

where you cannot find a job, where people are doomed to stagnate, where you simply cannot develop a career.

Verification of these opinions is all the more important because a significant part of graduates of Polish

universities are people from small towns and villages. Nearly 60% of graduates from the last five years are people

from small towns and villages; less than 23% come from cities with the administrative rights of a poviat (medium-sized

cities), and only about 17% live in the largest Polish cities (i.e. cities with over 500,000 inhabitants). Therefore,

it is fair to claim that the average graduate of a Polish university a resident of a small town.

In order to examine the economic situation of graduates who live beyond big cities after graduation, it is necessary

to ask some key questions:

- Do small town graduates develop professionally and improve their position on the labour market after graduation?

- How do they cope with the demands of a more challenging labour market with higher unemployment rates and lower wages than in larger cities?

- What picture emerges from comparing their situation on the labour market with the situation of graduates from large cities?

We have analysed the 2014 cohort of graduates – the only cohort for which we have the data covering the full period of five years after graduation. All the graduates in the group under analysis obtained their master's degree, i.e. they successfully completed 2nd cycle or long-cycle master's studies.

Even if we compare the most basic indicators we see that graduates from small towns and villages are more effective in finding a job than other graduates. The average job seeking period for graduates living in the country or in small towns is 3.95 months (compared to 4.31 months for graduates from big cities and 4.34 for graduates from the largest cities). Small town dwellers find their full-time jobs faster, too: it takes them 7.19 months on average (7.95 months for graduates from cities with administrative rights of a poviat (medium-sized cities), and 7.81 months for graduates from the largest cities).

Graduates from small towns and villages turned out to be as economically active as graduates living in medium-sized and large cities. On average they were employed for 89% of the time after graduation, similarly to graduates from big cities (89%), and slightly longer than graduates from medium-sized cities (88%). In terms of employment structure, graduates from small towns run their own businesses a little less frequently than the other graduates: on average they spent 9% of the period after graduation being self-employed, while the percentages for medium-sized and large cities are 10% and 11%, respectively. In turn, graduates from small towns work more often on a full-time basis, spending 78% of the period after graduation on this type of employment, compared to 76% in the other two groups of graduates.

We have also investigated the earnings and unemployment levels among the graduates from small towns. In order to ensure meaningful and reliable comparisons of wages earned in regions with different economic conditions, we used relative indices. These indices refer both earnings and unemployment levels to the situation on the local labour markets. The Relative Earnings Index (REI) is the ratio of the average earnings of a graduate to the average earnings in his/her area of residence, while the Relative Unemployment Index (RUI) is the ratio of the risk of graduate's unemployment to the unemployment rate in his/her area of residence. The indices offer a better way to measure the effectiveness of a graduate on the local labour market than direct values of earnings and unemployment level.

Although graduates from towns and villages earn slightly less than graduates from medium-sized cities (PLN 3,533 vs. PLN 3,606, respectively) and less than inhabitants of the largest cities (PLN 4,553), if we take into account the condition of local labour markets in terms of earning efficiency, graduates from small towns and villages do best across all the three groups : the REI for small town residents is at 0.91 of the average local earnings, compared to 0.82 in the case of medium-sized cities and 0.9 in the case of the largest cities.

The conclusions are similar as regards unemployment. Although the unemployment risk rate is the highest in small towns and rural areas (5.9% compared to 5.4% in medium-sized cities and 2.9% in big cities), graduates from small towns and villages tackle unemployment better than the other two groups, despite the challenges existing in smaller, local labour markets. The RUI for graduates from small towns is 0.65 compared to 0.81 for graduates from medium-sized cities and 0.69 for graduates from large cities.

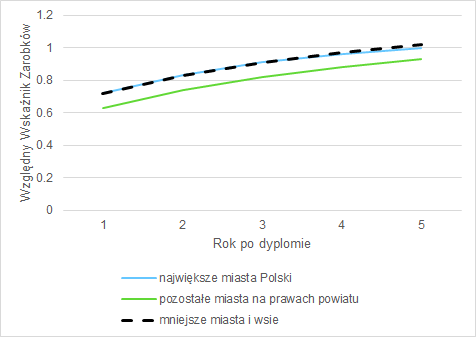

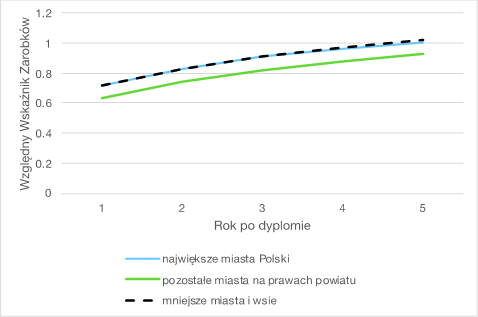

The following graphs show the dynamics of the relative indicators in the years following graduation. The graphs make it possible to dispel another myth which depicts the country and small towns as allegedly stagnant areas.

|

|

As we can see, regardless of the size of the place of residence, a similar trend is observed in subsequent years after graduation: each year after graduation, earnings of graduates from small towns go up consistently and, most importantly, they grow faster than the average earnings in the graduates' places of residence. Moreover, graduates from small towns and rural areas have proven to be systematically more effective in earning money than the graduates from the other two groups.

As regards unemployment, the conclusions are very similar: unemployment among graduates from small towns falls faster than it does in their places of residence. This trend, however, is observed across all groups of graduates, regardless of the size of their place of residence. Importantly though, starting from the second year after graduation, graduates from small towns and villages are most effective in avoiding unemployment.

Our analysis of the situation of graduates from different areas of education confirms the presented conclusions. In the case of each academic area of study in our analysis, graduates from small towns and rural areas achieved better results on the labour market than the inhabitants of medium-sized cities. For the most part, graduates living in smaller towns were also more effective on the labour market than inhabitants of big cities, regardless of the degree programme they studied, with social sciences and science as the exception: the graduates of these academic areas who live in the largest cities do better than their colleagues from small towns and villages. In other academic areas of study, graduates from small towns and villages perform better.